Bringing Copper Back to the Kitchen

Artist and author Sara Dahmen with her handcrafted copper

Artist and author Sara Dahmen with her handcrafted copper cookware.

Photograph courtesy of Sara Dahmen.

Sara Dahmen was doing a character study for an historical fiction novel she was writing in 2014 when she came to a realization that led her to copper. She was researching the average woman’s experience in the 1800s and realized that regardless of circumstances there was one place that was central to her life--the kitchen.

“No matter where she landed, her life was in the kitchen for a variety of reasons,” Dahmen says.

This realization led her to ponder the context of a 19th century kitchen and the cookware that would have been central to the functioning of it. She delved into what they were made of and where they would have been made, which had Dahmen comparing the answers to a modern day kitchen.

“They were not sent from China or Europe and someone would have made it down the road,” she says. “I realized that a lot of that was gone -- they are no longer made down the road or in the U.S.”

Dahmen was struck by all of the knowledge centered on locally crafted copper cookware that had disappeared. So the novelist set out to do something about it. With a professional life centered on writing at the time, initially her communications and marketing background were driving forces behind her idea to start a kitchen line centered on the principles of the past.

A selection of handcrafted House Copper cookware by Sara Dahmen.

A selection of handcrafted House Copper cookware by Sara Dahmen. Photograph courtesy of Sara Dahmen.

“I knew nothing about retail -- I knew nothing about manufacturing and had no mechanical background,” she says, of her initial intent to have a copper cookware line manufactured in the United States but not be involved in the actual building of the cookware.

Her approach changed when she met a tinsmith located fifteen minutes from her home in Port Washington, Wisconsin. Soon thereafter she started an apprenticeship to learn how to work with tin and copper. It was through this process that she came to a conclusion about the execution of her cookware line.

“I realized I don’t need to pay people to build this. I can build this,” Dahmen says. “It grew so organically.”

However, she soon learned that bringing copper back into the kitchen would come with its share of hurdles.

“Education was the biggest hurdle,” she says. “People had forgotten how to do it.”

Dahmen started networking to get some answers and support to enable her to fulfill her vision.

“It really wasn’t being done in the U.S., short of Brooklyn Copper Cookware,” she says. “Mack Kohler took me under his wing.”

Through this relationship, Dahmen said that Kohler, the founder of Brooklyn Copper Cookware, shared resources over the course of hours spent talking with him on the phone. Despite their cookware looking different from a design standpoint, the common ground they shared was a goal to bring copper cookware back to the kitchen.

Copper became the touchstone of Dahmen’s vision due to the qualities it brings to the cooking experience along with its minimal impact on the planet from the perspective of the throwaway cookware that is predominantly made this day and age.

“It conducts heat 25 times faster than stainless,” she says. “It can never go in a landfill -- it can be retinned forever.”

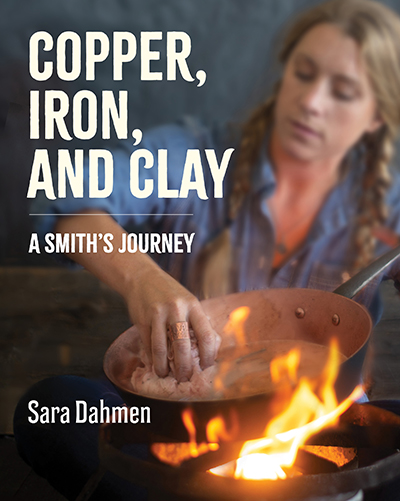

Cover image of Dahmen's book, Copper, Iron and Clay.

Cover image of Dahmen's book, Copper, Iron and Clay.Photograph courtesy of Sara Dahmen.

Copper’s place in history was the driving force behind the creation of her business, House Copper, in 2015.

“Along with pottery, wood, tin and iron, it was part of the historical pioneer American kitchen arsenal,” Dahmen says.

In addition to the handbuilt cookware Dahmen makes, she also offers retinning services and has found that it’s not uncommon for her to receive pots that were made in the late 1700s or 1800s.

“Copper cookware can last multiple generations if taken care of,” she says.

With people spending more time in the kitchen during the pandemic, Dahmen has experienced a huge spike in sales of her pots and retinning services, which, as a mom of three children, has made it challenging for her to keep up with demand given she is a one-woman operation.

She finds that some people contemplate the hefty price tag of copper cookware without considering the long-term benefits and savings.

“You can go and spend $25 on one piece of cookware and you will use it a couple of years and it will fail,” she says. “You will throw it in a landfill and then you will go and buy another one -- you are going to do that a lot for the ten pieces in your kitchen as it fails.

She said that in addition to contributing this waste to a landfill, people spend more money over time than if they had bought one or two pieces of copper that lasts hundreds of years. With so much emphasis and concern in America about where our food comes from, Dahmen would love for people to take the same approach to cookware, but she currently sees a disconnect.

“We care how the chicken is raised, we want cows that are grass fed,” she says. “As an extension of that conversation, ‘what are we cooking in?’ and ‘who made it?’ and ‘where was it made?’”

Dahmen stressed that if you can’t answer those questions, that’s a problem.

A copper baking sheet, handcrafted by House Copper.

A copper baking sheet, handcrafted by House Copper. Photograph courtesy of Sara Dahmen.

“A hundred years ago people could answer those questions,” she says. “I think that transparency is just as important as where you get your food.”

Dahmen, who didn’t own a copper pot prior to starting her business, shared some tips for getting acquainted with cooking with copper for anyone looking to transition to it. While she said you can use copper pots on an electric stove, she recommends gas as being most ideal due to the precision factor.

If just starting out with amassing a copper cookware collection for your kitchen, Dahmen recommends a one to three-quart cooking pot with a long handle as an ideal first piece. She notes that estate sales are an ideal place to locate used copper pots.

Dahmen said that when it comes to cooking with copper, people are mistakenly inclined to rev up the heat, but explains that’s not necessary because you don’t need as high of a temperature as you think you might need.

“You have to watch your food a little bit until you learn how your copper cooks,” she says. “The hardest thing is realizing you have faster and more efficient cookware.”

As for the care of the copper itself, Dahmen recommends using ketchup, lemon or vinegar on a regular basis to polish it up. Her preference is ketchup and she said that, while some polish theirs monthly, others, like her, might do it every three to seven months.

As far as Dahmen is aware, she is the only woman in America building and manufacturing copper cookware. While she builds much of her line by hand at her copper shop located at her mini farm, she has some pieces that are mass-produced in Ohio.

“I work with my neighbor who is an industrial designer and she will take my sketches and put them into a computer program if I want to mass-produce it,” she says.

Dahmen offers custom pieces in addition to pieces she consistently offers from her House Copper collection. One customer ordered a copper goat milking pail that Dahmen made from scratch to their specifications. Most recently she added a tin-lined copper cookie sheet to her line after a customer requested one and she saw how successful it was in making evenly baked cookies.

“The ones on the aluminum sheet were unevenly cooked on the bottom and the copper sheet ones were all even, consistent and golden brown,” she says.

To make her pieces, Dahmen sources her copper from Texas and her tin from Iowa.

“Some of the pieces are made for me and I am drilling, riveting, sanding, polishing, grinding and hand tinning,” she says. “I’m doing 80% of the work.”

Working with copper has come with its share of challenges for Dahmen, something she learned during her process of learning how to make cookware.

“So many components go into building it,” she says. “Copper is by far the hardest thing to figure out -- how to source it -- how it worked.”

She found a local foundry to pour cast iron handles for her cookware.

“They are ductile iron handles that have been heat-treated,” Dahmen says. “The way copper heats and cools so fast, you want a type of iron that is not so brittle, so that it can expand and contract faster and try to keep up with the copper it’s sitting next to.”

She stressed that this is the same reason you have to use copper rivets when making the cookware.

“They are the bridge and they have to expand and contract with the body of the pot,” she says.

Dahmen explains that copper handles stopped being put on pots in the late 1700s because they would get hot so fast and would be soft and therefore tended to bend, crack or get misshapen.

“That’s when it went out of fashion, as soon as pouring iron became more affordable -- cast iron handles were seen then,” she says.

Dahmen uses early 19th century tools when handbuilding her cookware.

“Sixteen to twenty-four ounce copper is the thickest I can do with the tools from the early 1800s,” she says, adding she uses other tools when using thicker material. “I use 3 mm for a cookie sheet -- that is the thickest I can hand turn myself over the tinsmith stakes.”

The piece in Dahmen’s line that’s the biggest seller is her 12-inch skillet that weighs almost 8 lbs.

“It’s insane how much it weighs,” she says, adding that a light “copper” pot you come across is most likely aluminum sprayed to look like copper.

In April, Dahmen’s most recent book, Copper, Iron, and Clay: A Smith’s Journey (William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins), was published. In the memoir, she shares the story of how she got to be a coppersmith, along with the history, science, use and care of the three kinds of cookware that has been with us through the centuries. It also includes recipes.

Dahmen has enjoyed learning how copper cookware has evolved over the centuries. Aside from researching the designs of pots from the 1800s in books, she goes to see them in museums or will get an original piece to study.

“It’s fun to see how copper cookware has evolved,” she says.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Bringing Copper Back to the Kitchen

- Pat Musick: Inspired by the Nature of Copper

- Kenoka Wagner: Creativity Knows No Boundaries

- 11th Annual Flying Horse Outdoor Sculpture Exhibit Unveiled